Feel the wrath of wheat!

Rick Riordan

How much wheat do you eat?

Ask yourself this question: how much wheat do you eat? You’re probably having it for breakfast with cereal and toast. Sandwiches for lunch. Pasta, pies or couscous for dinner? Perhaps even the occasional biscuit or slice of cake. It’s even used to thicken sauces and gravies. Chances are that you’re eating wheat daily.

Wheat-based products are convenient, inexpensive and quick to prepare during busy working days. What’s not to like?

It’s not just in our food, though. Wheat can also be found in cosmetics, supplements and medication. It’s prevalent in food additives. Whenever you see the ingredients glucose, maltodextrin and dextrose, these all come from wheat-based sugars.

Gluten.

Most people will have heard of gluten. Any baker will know that gluten is a protein that makes the dough smooth and elastic, creating that open-crumbed texture in a good loaf of bread.

Gluten is a type of protein classed as lectins. Lectins are anti-nutrients that plants employ to defend themselves from being eaten. For example, lectins are present in unripe fruit. The seed is undeveloped, so the plant does not want them to be eaten. Once the fruit is ripe, the lectin disappears, and animals are encouraged to eat the fruit and swallow the seeds of the fruit whole, to be dispersed elsewhere where they can germinate. Some plants do not want their seeds to be eaten, grains for example. These plants want their seeds to fall to the fertile ground and grow the following year when the current grasses die off over winter. They employ chemical warfare in the form of lectins that attach themselves to sugar molecules. In wheat, this lectin is a type of gluten called Wheat Germ Agglutinin.

The porous gut lining allows digested nutrients to be absorbed into the bloodstream. Gluten attacks this lining, “punching holes” into it, allowing undigested food and gluten into the bloodstream. This condition is known as “leaky gut”.

People have varying levels of tolerance to gluten, and many won’t even know they have an intolerance. Whilst celiac disease is a hyper-sensitivity to gluten and can cause digestive problems and gastrointestinal symptoms, there are other common symptoms of gluten intolerance, such as weight gain, brain fog, bloating, back pain, migraine, asthma, panic attacks and depression. Gluten intolerance could be behind any number of symptoms. Pharmaceutical products are often prescribed to address these symptoms.

Certain plants have developed chemical defences against being eaten, but we still have our counter-defence mechanisms. We have strong stomach acid, a mucous lining of the intestine and gut bacteria to protect us from many of the effects of lectins. Unfortunately, these defences can be overwhelmed by the onslaught of gluten, particularly from wheat, and the barricades are breached.

But humans have been consuming wheat for centuries, so why are the problems described above a modern phenomenon? For that, you must understand how wheat farming and bread production have evolved. Wheat has changed dramatically and no longer resembles what it used to be many years ago.

The evolution of wheat.

The development of agriculture allowed civilisations to flourish. Wheat was easily stored, didn’t readily spoil, was transportable and had a high calorific content. The earliest form of ancient wheat grain was “Einkorn”, cultivated during the Neolithic and the Bronze Age. The second oldest wheat cultivar was “Emmer”, derived from a natural hybridisation of Einkorn and wild grasses. Khorasan and Durum wheat are derived from Emmer. Spelt is a more widely known early grain and was likely hybridised from Emmer and other wild grasses.

These ancient kinds of wheat had a much taller stem than modern wheat, measuring around 160 cm in height, which is over 5 ft tall. These stems tended to break before the grains were fully ripened if fertiliser was applied, so hybridisation would always strive for a shorter and stronger stem.

The mid-20th Century saw a “Green revolution” to hybridise wheat to create a short, strong stem with a high grain yield to feed a starving world. This work was spearheaded by an American agricultural scientist called Norman Borlaug. He experimented with novel varieties of wheat by inducing genetic mutations in plants. The aim was to produce higher-yield, disease-resistant varieties that could be grown in harsher climates. This hybridisation was far from anything that would occur in nature. The result was a wheat with five to ten times more yield per acre – significantly more profit for the producers. So, it was a tremendous commercial success.

The problem is that no safety studies were conducted on the fitness of this modern hybridised wheat for human consumption. The gluten of ancient grains is much more fragile in structure and easier to digest than that of modern grain. That’s not to say that our ancestors didn’t experience problems from consuming this wheat – archaeological evidence found in mummified pharaohs revealed that they also suffered issues with gluten – it just wasn’t as prevalent as nowadays.

Modern farming.

The Green Revolution altered arable farming, creating a monoculture landscape increasingly dependent on nitrogen fertilisers to drive yields. Herbicides, pesticides and fungicides became widely used. Ironically, the shorter-stemmed wheat was ineffective in shading out the weeds, so more herbicides were employed. This had a detrimental impact on the health of the soil, resulting in the depletion of many minerals and nutrients.

One particularly toxic spray used is glyphosate. In 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer declared glyphosate as “probably carcinogenic.” Glyphosate inhibits the “Shikimate pathway, ” a metabolic process used by bacteria, fungi and plants but not found in animal cells. For this reason, the manufacturers claim it is safe for humans, but this ignores the fact that we rely on the function of gut bacteria for healthy digestion and a healthy body. 90% of our neurotransmitters are made in the gut, affecting our brain health.

Glyphosate impacts the micro-organisms in the soil, which the plant needs to take minerals and nutrients into the plant. It is little wonder we are now deficient in many of these nutrients.

Modern bread-making.

It’s not just farming that has changed so too has the bread-making process. Bread-making used to be a labour of love, taking a couple of days to complete. There was no commercial yeast, only the naturally occurring yeasts in the air. This slow “sourdough” fermentation process breaks gluten proteins down and eliminates most anti-nutrients. This fermentation did a lot of the digestive work for us, making traditional sourdough breads much easier on the gut.

In the 1960s, a faster bread-making process was developed, known as the “Chorleywood” method. This method incorporated more yeast and added fats and chemicals with high-speed mixing. Turning flour into baked, sliced, and packaged bread within 3½ hours was now possible. By 2009, around 80% of the bread produced in the UK employed this method. The rapid fermentation didn’t allow the yeasts to break down the gluten as effectively as traditional proving.

The food pyramid.

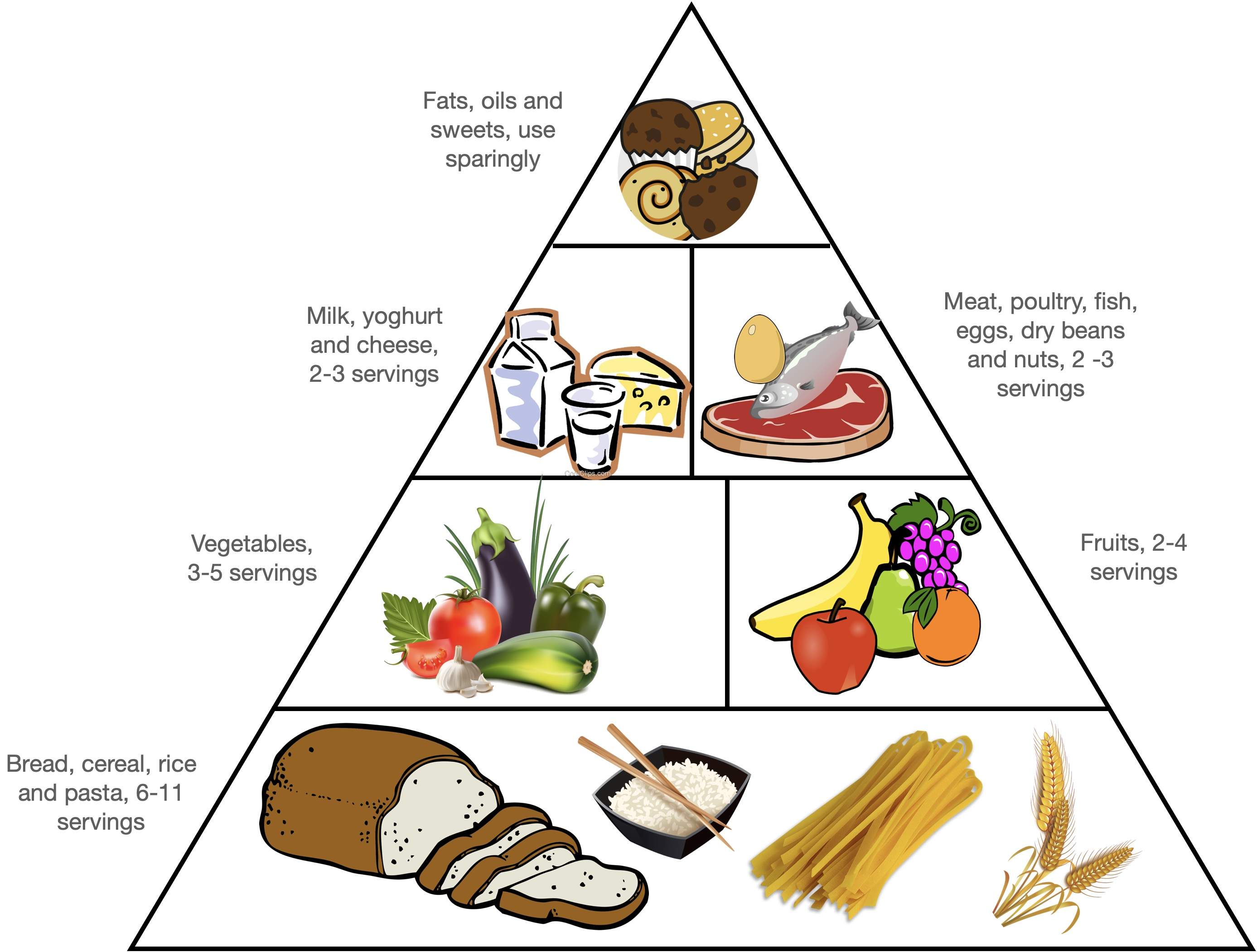

Another significant recent development is the production of the food pyramid. This was first developed in Sweden in the 1970s and adopted by the US Department of Agriculture and similar organisations worldwide. The food pyramid provided Government advice on healthy eating. As you can see from the diagram below, the advice was that most of our calories should be obtained from eating starchy carbohydrates such as grains. At the top of the pyramid were fats, which were advised to be limited. I covered this more in my blog “Dietary Fats”. I won’t repeat it here, but the impact was that people were encouraged to eat more grains and less fats.

The impact on our health.

The combination of a more robust gluten structure, more chemicals in wheat production, rapid bread production and official advice to increase our consumption of grains has had a striking impact on our health. People have become fatter and sicker.

It’s not only the gluten that causes health problems. So do the sugars in wheat. The increased consumption of modern wheat has led to a dramatic increase in Insulin Resistance and Diabetes.

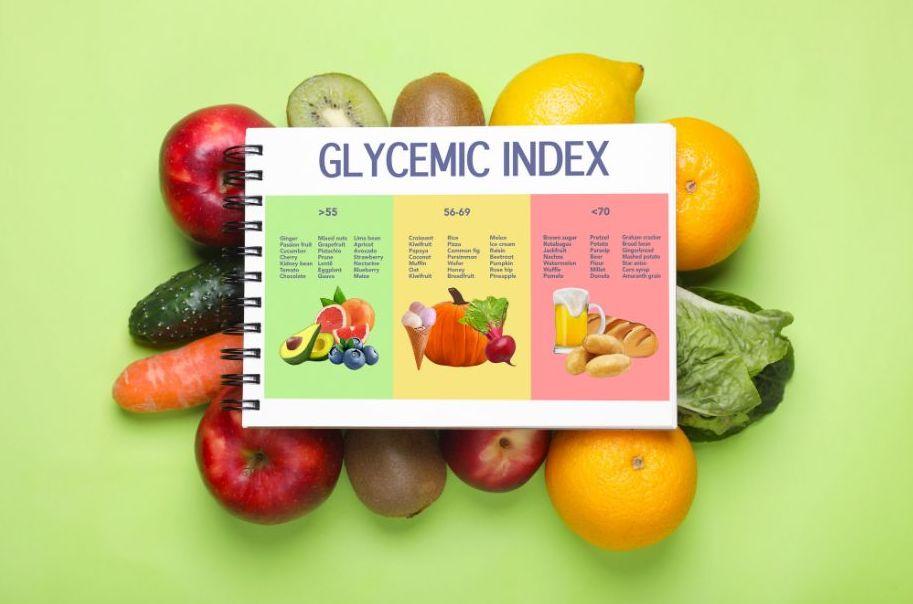

The Glycemic Index (GI) measures the rise of blood glucose levels two hours after eating foods. The higher the blood glucose levels, the higher the insulin response.

Insulin Resistance and Diabetes.

It was a big shock to me to learn that bread has a higher GI rating than table sugar. You read that right. Eating bread provokes a more elevated and faster blood sugar response. The GI index rating for table sugar is 59. For white bread, the GI rating is 69, whilst whole wheat bread is higher still, with a rating of 72! So much for the notion that whole wheat bread is better for you (although wholegrain wheat does have more B vitamins).

The reason for this is that modern wheat contains higher amounts of a type of carbohydrate called “Amylopectin A”; the molecular structure of this causes a high and fast blood sugar spike. Carbohydrates high in Amylopectin B, such as potatoes and bananas, produce a blood sugar spike that is not quite as high and fast. Carbohydrates high in Amylopectin C, such as beans and pulses, have a lower and slower blood sugar response.

Given the amount of wheat in the modern diet, as encouraged by the food pyramid guidance, it is little wonder that more people are developing Insulin Resistance and Diabetes.

Gluten-free products.

Given the increasing awareness of issues caused by gluten found in modern wheat, it’s little surprise that food manufacturers have seized the opportunity to provide gluten-free products as a marketing strategy. Take a look at your local supermarket – chances are that they have a dedicated area to providing gluten-free alternatives for breads, crackers, cake and biscuits.

Whenever I advise clients to avoid wheat for a while, I am often asked whether they should start eating gluten-free alternatives. My response to this is, “Read the ingredients”. Here are the ingredients for a leading brand of gluten-free bread:

Water, Starches (Tapioca, Maize, Potato), Rice Flour, Bamboo Fibre, Yeast, Maize Flour, Rapeseed Oil, Dried Egg White, Psyllium Husk, Vegetable Glycerol, Caster Sugar, Salt, Hydroxypropyl Methyl Cellulose, Xantham Gum, Calcium Propionate, Potassium Sorbate, Natural flavourings.

Sounds yummy, doesn’t it? The problem with many gluten-free substitutes is that they are still high in carbohydrates, often highly processed and contain preservatives, additives, starches, binders and fillers. I would think very carefully before switching to these products.

Wheat and Kinesiology.

When I first had a kinesiology treatment, I was shocked to hear that I had a sensitivity to wheat and was advised to stop eating it for a while. I was desperate to get well again, so I did. After three months, the kinesiology testing found that my gut had healed, and I could tolerate wheat again in small amounts. My digestion had improved enormously, and the following summer, I found that I no longer suffered from hay fever, which had been with me since I was a child.

Before that, I used to eat a lot of wheat. Every Friday night was pasta night; Spaghetti with tuna and tomato sauce was my favourite. Within a couple of hours, I would always feel bloated, which I used to put down to the tomato sauce. Nowadays, I don’t suffer that reaction on the rare occasions I eat pasta. I am still sensitive to wheat but can tolerate it in small amounts. I’m mindful of when I eat it and enjoy it when I have it.

Whenever I get a new client, I test for wheat sensitivity. The overwhelming majority of clients demonstrate some level of sensitivity. Either they cannot currently tolerate it at all, or they can tolerate it in small doses. Occasionally, I find clients with “cast-iron” guts who have no sensitivity to wheat at all, but this is rare. For those clients who currently cannot tolerate it, I advise them to cut wheat from their diet for a period, allowing time for their gut to heal. I aim to get the client to a point where they can tolerate wheat in limited amounts without impacting their health. Some can never tolerate wheat.

One such client suffered from a severe case of Ulcerative Colitis for five years. She faced having her colon surgically removed. I tested her for wheat and found that she was sensitive. This surprised her as she had an allergy test for wheat, which proved negative. Whilst wheat didn’t cause an allergic reaction, her body could not tolerate it. She recovered and did not require surgery, but she had to eliminate wheat from her diet.

Should you give up wheat?

Everybody is unique and reacts differently to wheat. Whenever I find a sensitivity to wheat in a client, I aim to get them to a point where they can tolerate it in small amounts, if possible. I never want to tell clients they shouldn’t have a particular foodstuff again. I’d much rather get them to a point where they can have some of what they fancy now and then.

Those clients who can’t tolerate it usually decide to give it up when they experience the health benefits. They often try a bit of wheat again and realise it makes them feel unwell.

For others who get to a point where they can tolerate wheat again, then there’s no need to give it up altogether. Like me, they should be mindful of the amount they eat, and if they start to develop symptoms such as bloating or brain fog, then refrain from eating it until symptoms improve and perhaps eat less. As I said, everybody is different.

One consequence of giving up wheat is that it alters our gut microbiome. The Bifidus bacteria in our gut help break down wheat gluten into amino acids. Bifidus is present in breast milk and raw milk (as well as probiotics). Another reason our ancestors coped with wheat better, apart from the less aggressive glutens in ancient wheat, is that they drank raw milk. Our milk is now pasteurised, so the Bifidus bacteria is not present. Bifidus bacteria are also harmed by antibiotics and chemicals, which are more prevalent today.

If you give up wheat altogether, the Bifidus bacteria disappear, increasing digestion problems of any food containing some wheat. So, an argument can be made for eating small amounts.

Through muscle testing, Kinesiology can detect any sensitivity to wheat (the medical profession has no official test for non-celiac gluten sensitivity). If you can tolerate wheat, then I would give the following advice:

- Reduce the amount you eat; give your body time to recover. Despite what the food pyramid advises, wheat should not form the basis of all your meals.

- Choose products made from older grains where possible, such as Spelt or Khorasan. These are becoming more widely available.

- Don’t eat commercial bread. Find a good baker who makes proper sourdough bread.

- Consider supplementing with digestive enzymes and probiotics. Kinesiology can help identify which works best for digesting wheat.

- Eat organic produce where possible.